Sanitify III: What is treatment resistance?

One of the most vexing questions in mental health care.

Is there such a thing as a 'difficult' or 'treatment-resistant' patient? Earlier this week I came across a post by psychotherapist Giovanni Felice Pace challenging these labels. The crux of Felice Pace's argument was:

- There are no difficult patients. "When we meet a patient who won’t 'move', who won’t 'comply', it is not they who are blocked. It is us [therapists]. It is our inability to bear what they bring, to stay with the silence, to hold the unbearable, to listen past the noise of our own ego."

- However, the idea of a resistant patient is as old as therapy itself. According to this paper: "More than a century ago, Freud used the term 'resistance' to describe unconscious mental reactions and behaviour exhibited during psychoanalysis that inhibited the response to therapy."

- In psychiatry, resistance denotes the lack of symptom reduction despite treatment. The above paper adds that the concept was "crystallised in the 1980s, with the demonstration of clozapine’s efficacy over chlorpromazine in patients with schizophrenia, whose illness had not responded to at least three previous antipsychotic trials."

- According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, treatment-resistant depression affects 30% of people living with major depressive disorder.

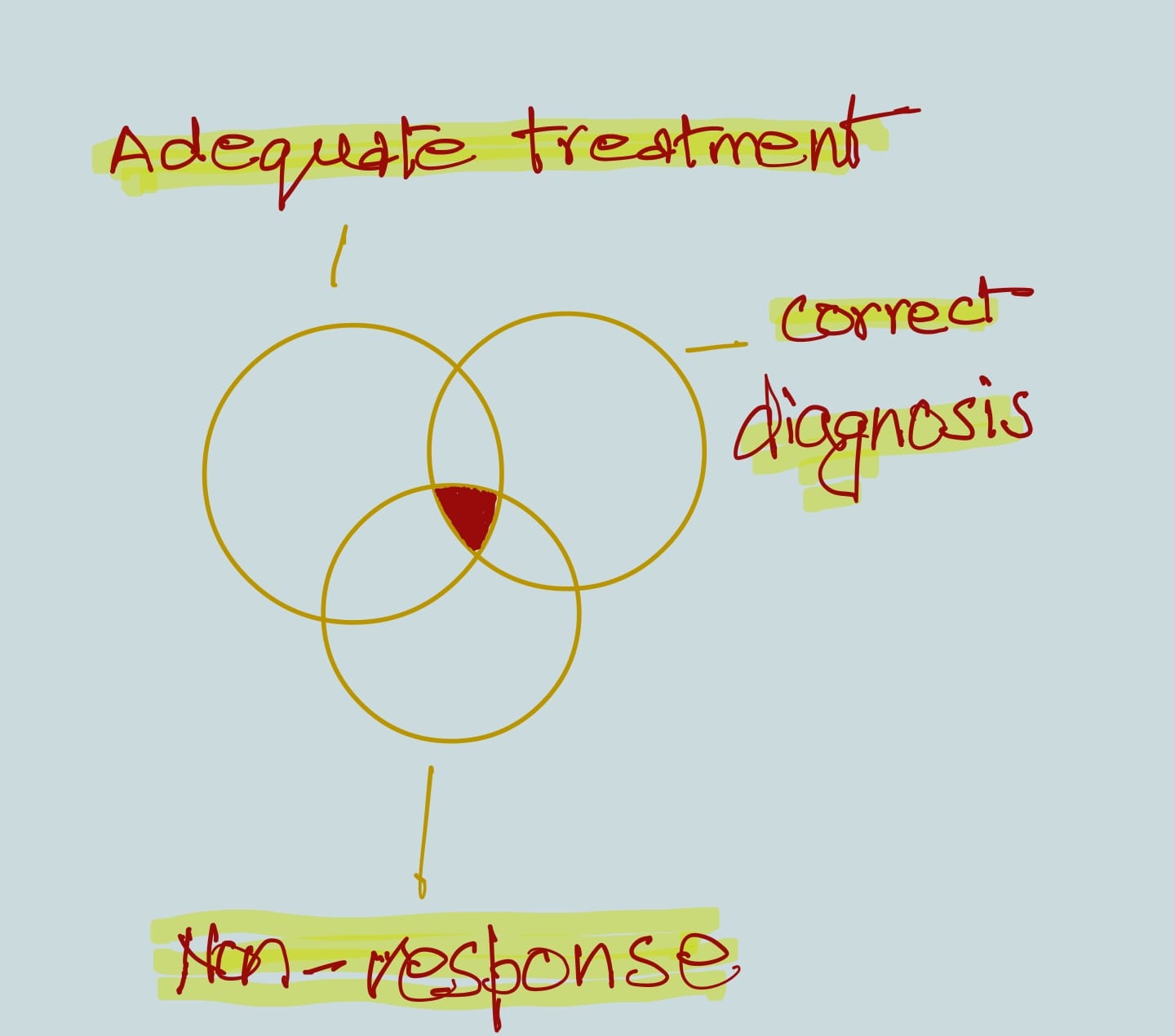

- The presence of three conditions is necessary to pass the verdict that a patient is demonstrating resistance:

i) A correct diagnosis

ii) Adequate treatment

iii) Non-response to the treatment. - If the diagnosis is wrong or the treatment offered hasn't been optimum, then it's a case of misattributed or 'pseudo-resistance'.

- Different mental health conditions – depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, etc – have different criteria and lines of treatment for treatment resistance.

- However, the paper points out that there exist significant problems in how these criteria are set. For example:

i) The number of treatment trials that a patient should receive prior to a diagnosis of treatment resistance is, for some criteria for OCD and depression, either not defined or inconsistent, ranging between 2-3 different drugs for depression.

ii) Certain criteria for schizophrenia, depression, and OCD recommend using different drug classes (eg, ensuring a trial of first- and second-generation antipsychotics in some criteria for schizophrenia), while others do not make this specification. - These discrepancies make treatment resistance one of the murkiest questions in mental health care.

- In her book When Psychotherapy Feels Stuck, Mary Jo Peebles describes how a patient can develop hope, the prerequisite for the resistance to break down and the work of meaningful change to begin:

"A person walking into a psychotherapist’s office for the first time wants to feel better when she walks out. We want her to feel better too. But how is her sensation of feeling 'better' related to change? To feel better, connection is essential. Our patient needs to feel this stranger, her potential therapist, grasps something about who she really is and what she is trying to say. There needs to be a 'click.' The therapist’s competence is in play as well. Our patient needs to feel the person she is entrusting herself to has experience with what she brings and will be able to help her."

Peebles says connection and competence working together creates hope. - The question is, does a framework like this, an understanding of resistance negotiated through the therapist's 'competence', place an exclusive and unfair burden on them? Can it turn into a case of 'blaming the therapist'?

- Psychotherapist Mark L Ruffalo disagreed with Felice Pace's argument. "Of course there are difficult patients," Ruffalo said, "whose problems tend to pervade and saturate all relationships, including the treatment relationship.... This is not to discount the importance of examining ourselves but rather to highlight the danger of 'blaming the therapist'... for the pathology that is internal to the patient."

- On the other hand, labelling some patients as difficult can be weaponised to ghettoise or institutionalise them. They can be declared hopeless and unworthy of care. This is a real risk given the balance of power in a clinical relationship tilts heavily in favour of the clinician.

- Due to stigma and social ostracism, many patients feel a lack of agency even before they show up in the clinic. Calling them resistant could further deepen feelings of helplessness and self-blame.

What is your view on treatment resistance? Have you ever been labelled difficult or resistant? Write to me and I will publish your thoughts in a future edition.