🛎️ Live: My Oxford paper on media, money, and mental health

How to fix the glaring hole in the booming news coverage of mental health.

Thank you, and hope next week brings good energy to all of us. - Tanmoy

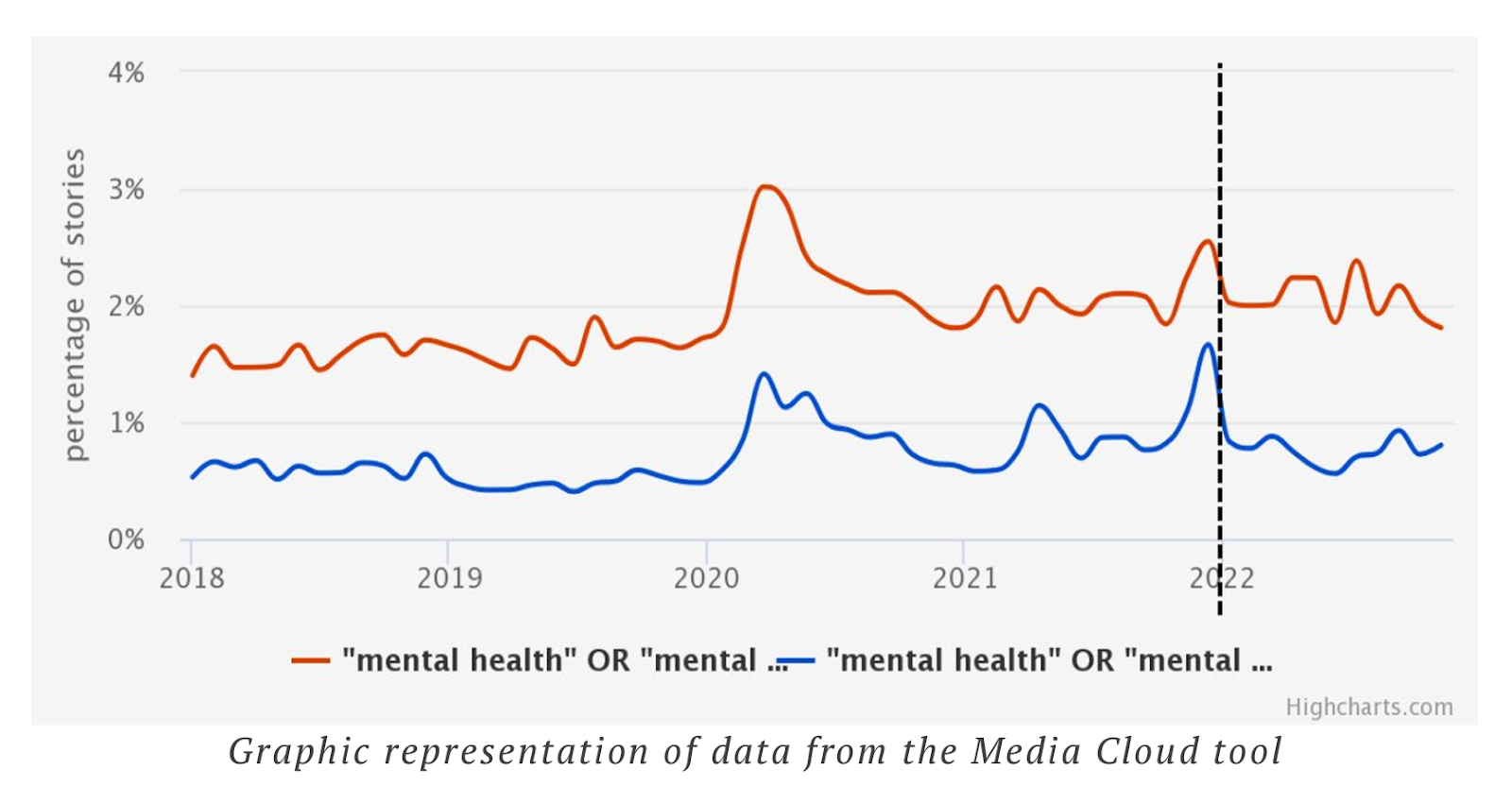

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant increase in mental health news coverage, indicating an explosion of public interest in the topic. As part of my fellowship at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford, I carried out a comparative analysis of mental health coverage in global and Indian English-language media before and after the pandemic. The analysis – likely the first of its kind – showed that the number of stories with mental health-related themes had more than doubled in this period.

- Globally, English-language stories with mental health-related keywords jumped 166% with the onset of the pandemic: from 1.4% of total stories in January 2018 to 3.02% in March 2020 at the start of lockdowns.

- Across Indian English-language media the proportion of stories containing mental health-related keywords grew from 0.53% in January 2020 to 1.41% in March 2020 (+115%).

- The average number of such stories leading up to January 2022 stayed significantly above trend line for 2018 and 2019, both globally and in India.

Date range: According to World Health Organization, the first cluster of cases of pneumonia, eventually attributed to the novel coronavirus, was announced in Wuhan, China, on December 31, 2019. 30 For my analysis, I examined a period of two years prior to that date, beginning on January 1, 2018, and almost three years thereafter, ending on November 6, 2022, which was the most recent date with accessible data.

Source: Original research using the Media Cloud tool developed by the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Northeastern University, and the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. The tool monitors fluctuations in media coverage of subjects over time.

As anxieties over the pandemic eased in most regions of the world over 2022, media attention to mental health-related stories stabilised to pre-pandemic levels. But the expanded space for mental health in public imagination has, hopefully, left a lasting cultural impact.

The surge in coverage presents an opportunity for the media to tell powerful stories on a subject that touches everyone. But it also raises thorny questions about the social role of mental health journalism and the current state of reporting on the topic.

Media stories overplay clinical or medical solutions, including, more recently, ‘therapy’ apps, which end up individualising the problem.

Dr Valentima Iemmi, fellow, Department of Health Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science

Follow the money

Mental health stories have historically constituted a minuscule share of the overall volume of stories in English-language media. Until the pandemic, media interest in mental health was largely limited to obligatory articles on World Mental Health Day. And even this tepid coverage was often crude, sensational, and dehumanising, perpetuating stigma and discrimination through negative stereotypes of mental illness such as dangerousness, criminality, and unpredictability.

While the pandemic triggered an increase in the volume of stories – and social attitudes are showing promising signs of change, thanks largely to advocacy by lived experience experts – a close study of the coverage reveals that there remains a critical missing theme in mental health journalism: the unjust economics of global mental health.

Global mental health is an emerging field that aims to alleviate mental suffering and promote mental health worldwide. It seeks to address the historical oppression and exclusion of marginalised communities from mental health care and advocates for equitable access to mental health resources, which are disproportionately controlled by rich Western countries.

An overemphasis on Western perspectives has erased the lived realities and needs of people in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) — home to 80% of the global population, and by some estimates, 80% of people who live with mental illness. Here's some data from the World Mental Health Atlas on the disastrous inequality this has bred:

- 75% of people in LMICs with mental, neurological, and substance use disorders receive zero treatment.

- In 71% of low-income countries people pay out of pocket for psychotropic medicines. The figure is 2% in high-income countries.

- Globally, the median number of mental health workers is 13 per 100,000 population. It’s over 60 in high-income countries. And below two in the poorer countries.

- The median number of mental hospital beds per 100,000 population is over 25 in high-income countries. It is below two in the poorer countries.

It is brutally clear that the concept of equity at the heart of the global mental health movement has not translated into change on the ground. And the media has largely failed to keep up with this important story.

It is critically important that the media understand the economics of mental health. The history of the mental health sector is linked to money and class.

Raj Mariwala, director, Mariwala Health Initiative

Ditch the dominant model

Instead, mental health coverage in the media has been dominated by the Western biomedical model, which, crudely put, views mental illness as an individual’s problem caused by imbalances in brain chemicals.

This perspective overlooks the deeper socioeconomic stressors such as poverty and inequality that contribute to mental health issues like depression — the leading cause of disability worldwide. It also leads to shallow policy approaches focused only on medical "cures".

“For more than a generation now, we in the West have aggressively spread our modern knowledge of mental illness around the world,” writes US journalist Ethan Watters. “We have done this in the name of science, believing that our approaches reveal the biological basis of psychic suffering and dispel prescientific myths and harmful stigma. There is now good evidence to suggest that in the process of teaching the rest of the world to think like us, we’ve been exporting our Western ‘symptom repertoire’ as well. That is, we’ve been changing not only the treatments but also the expression of mental illness in other cultures. Indeed, a handful of mental-health disorders — depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and anorexia among them — now appear to be spreading across cultures with the speed of contagious diseases. These symptom clusters are becoming the lingua franca of human suffering, replacing indigenous forms of mental illness.”

When the Western media does cover health issues in LMICs, it often focuses on communicable diseases and "exotic disease, disaster, and despair stories", neglecting non-communicable diseases like mental illnesses and the glaring disparities between high-income countries and LMICs.

To be fair, the media faces several challenges when engaging with mental health and its economic aspects. The inherent complexity of mental health, lack of awareness among journalists, limited reliable data, and the prioritisation of breaking news stories hinder comprehensive coverage of the economics of the mental health sector.

To rectify these historical omissions, I propose four foundational areas for the media to focus on:

- The flow of money into the mental health sector,

- Who benefits from it,

- Who is left out, and

- At what cost.

The full paper, available here, includes four chapters that delve into these topics, including insights from key stakeholders such as reporters, editors, mental health funders, and academics studying global mental health.

You're not going to be able to tell 100 stories about 100 people, but you can use 100 data points to tell an impactful story.

Riddhi Dastidar, journalist

TL;DR

For those without time to read the full paper, I highlight five lessons in improving mental health coverage.

Lesson 1: Reimagine mental health beyond healthcare

To effectively address any public health challenge, our conversations must extend beyond healthcare and encompass socioeconomic forces. The media can engage public health experts to explain how various systemic and structural factors, such as financial stress, housing crises, job insecurity, and the loss of green spaces impact mental health. Creating space for lived experience experts and promoting diversity within newsrooms are also essential for a nuanced understanding of mental health.

Lesson 2: Change the narrative and presentation of mental health stories

Avoid oversimplification when reporting on complex themes like mental health. Instead, embrace nuanced storytelling that shuns simplistic solutions. Present mental health stories on your platform in a way that reflects their cross-cutting nature, breaking free from traditional classification systems that limit their reach.

Lesson 3: Provide training to reporters and editors

Journalists covering mental health should have a basic understanding of business and economics, while those in finance or economics should familiarise themselves with the health domain. Interdisciplinary knowledge allows journalists to grasp the decision-making processes, budget allocations, and systemic deficiencies that influence mental health outcomes. Newsrooms should curate and provide easy access to relevant resources to support journalists in their coverage. (See Appendix 1 of the paper.)

Lesson 4: Look beyond large sums and glamorous characters

The media's penchant for big-dollar figures and big-name philanthropists investing in mental health can be limiting. Instead, investigate how funds are distributed and whether they contribute to sustainable reforms and capacity building. Newsrooms should emphasise the "why" and "how" of mental health funding rather than solely focusing on the “how much”.

Lesson 5: Prioritise inclusion and equity for scale and impact

The ultimate goal is to tell stories that drive home the urgent need for equity and inclusion in mental health. Emphasise the need for both more resources and their effective and equitable utilisation.

Better mental health journalism requires addressing the harmful history of coverage, challenging overly westernised and medicalised narratives, and foregrounding the socioeconomic factors that influence mental health.

By improving coverage, the media can play a crucial role in reforming public attitudes, reducing stigma, and promoting a more equitable and just approach to mental health worldwide.