It's time to drop suicide from cricket's vocabulary

Suicide cannot be a metaphor to describe (sporting) blunders. The game I love needs to take the lead.

Trigger warning: suicide

Few mistakes in sport provide as much material for mockery as run-outs in the game of cricket. The batter hits the ball and starts running, confident of covering the 22 yards to the other end of the pitch before a fielder can retrieve the ball and break the stumps. But it quickly dawns on them that they have fatally underestimated their opponent, that their confidence was really hubris.

The dismayed batter now has two choices: dive desperately to salvage some honour, or give up running and meekly surrender to their fate. Both outcomes are embarrassing.

The comic potential of run-outs was most famously embodied by former Pakistani captain Inzamam-ul-Haq, known for his legendary clumsiness between the wickets (no less than his sublime batting skills). Whether or not you know anything about cricket, I highly recommend this selection of Inzie's hilarious run-outs:

To be fair, Inzie was merely the run-out's most prominent exemplar. Of all the ways you can get out in cricket, the run-out draws the loudest jeers because it is seen as a brain fade on the batter's part – a shameful lapse in judgment unbecoming of an elite athlete, an irresponsible act of self-sabotage.

Or, as cricket commentators and writers habitually describe them, run-outs are 'suicidal'.

What's in a word? Sometimes an entire school.

Like millions of Indians who grow up fetishising cricket, the game's vocabulary shaped my consciousness too. Unattainable college crushes left me clean bowled. I faced a tyrannical senior with a straight bat. At the time, this fanboy language felt effortlessly natural. There was nothing odd about any of it. Why would the run-out's comparison with suicide be any different?

For an entire generation, live cricket commentary was the only occasion the word 'suicide' was heard in public without an awkward hush accompanying it. In thousands of hours of watching cricket, my favourite commentators likened absurdly funny run-outs to suicide (some invoked hara-kiri, Japan's ritualised form of suicide) hundreds of times. It was impossible to be confused about what the word was supposed to connote – a monumental blunder that you laugh at.

But then, my initiation into cricket took place in the 80s and 90s. It was a different world. Stories of sportspersons killing themselves out of stress, or halting their careers because of the performance pressures brought on by what was to become an extension of the entertainment industry, were silenced into non-existence.

There was no Naomi Osaka or Simone Biles. There was no Robin Uthappa, confessing he had contemplated jumping off the balcony. No Jonathan Trott, saying he had 'considered driving my car into the Thames or into a tree'. No Praveen Kumar, who almost shot himself in the head. No Sarah Taylor speaking about her struggles with anxiety and fear of flying her entire career. No Ben Stokes or Glenn Maxwell taking sabbaticals from the game at the peak of their powers, reclaiming the right to be human over heroes. There was no bio-bubble fatigue and no threat of terror attacks.

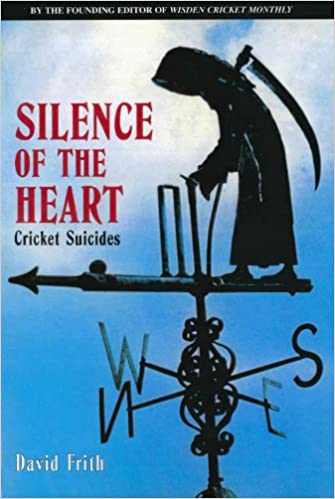

There was no David Frith either when we started watching cricket, so we had no way of knowing that of all sports, cricket has arguably the most shocking correlation to suicide.

Cricket in my childhood was about high-pitched emotions, not refined sensitivities. You did not expect the powers in the game to make political statements or champion justice and equality. For instance, watching cricket 20 or 30 years ago, hoarding centrefolds of swashbuckling supermen, you couldn't have dreamed that the word 'batsman', the most glamorous designation in the sport, would one day be abolished from the game's lexicon in favour of 'batter'.

As I realised a couple of days ago while teaching my 3.5-year-old son how to hold a bat – that's an entire school right there compressed in a solitary language change.

That same evening, during an IPL game, I heard a commentator describe a near-run out as 'suicidal'. I was familiar with the exasperation in his voice, the harmless drama he probably thought he was belting up, or perhaps it was pure reflex action. But this time, it bothered me.

The game I love must stop using suicide as a metaphor, using its clout to send a message to other fields – politics, business, art – where the word's casual misuse is rampant.

If not now, when?

Where do we begin? The IPL is a great place.

The Indian Premier League is the richest franchise-based cricket tournament in the world. This year, the annual T20 league's brand value was estimated at over US$6 billion. (Update: In 2024, that has reportedly surged to over US$10 billion.) Its television viewership routinely crosses 400 million. IPL 2021, the league's 14th edition which resumed earlier this month in the UAE after a Covid-induced disruption in India, has reportedly recorded 242 billion minutes of content consumption on the official broadcasting network. (Update: At the halfway stage of the 2024 edition, IPL's TV viewership created a new record.)

The IPL is a pop-culture juggernaut with enormous influence.

Hidden among all the superlatives routinely associated with the tournament is one little piece of data: the 15-21 age group is now the biggest contributor to IPL's burgeoning viewership.

This coincides with the demographic most vulnerable to suicide. Suicide kills more Indians in the 15-35 age group than any infectious disease or heart condition. The only thing that would be embarrassing, shameful, and irresponsible is cricket ignoring this reality.

Agree with the below.. Language is very important.. I was watching ENG vs NZ wc 19 final and a certain term used by the commentators triggered a panic attack 😭😭 https://t.co/4BoaBAQtWj

— पियूष(P!¥u$h) (@_din_djarin_) October 2, 2021

This is the week's bonus piece. If this article has resonated with you, do share it widely. Tag your favourite cricketers and commentators on social media and request them to start a conversation. Start a hashtag. Do what you can to spread the word. And please support my independent mental health storytelling. Thank you.

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this article, this website provides contact details of free helplines around the world.