The miracle no one asked for: how 2020 cured my (our) awful holiday depression

The holiday season brings out my darkest moods. But in a year where trauma overwrote trauma, I finally became free.

Prelude: homecoming

December 31, 5.50 pm, Durgapur. Prem jegeche amar mone, bolchi ami tai/tomay ami bhalobashi, tomay ami chai. Passion is stirring in my heart, that’s why I say/I love you, I need you.

Somewhere in the neighbourhood of my childhood home, they’re blasting the racy Bengali hit from the 90s on loop. It’s the prelude to tonight’s year-end ‘feast’, a word used in this part of the world to describe open-air winter-night picnics, where people in wind cheaters and monkey caps cook and eat mangsho-bhaat — meat and rice — and dance badly to loud, kitschy music.

Delhi, where I’ve spent almost my entire adult life after leaving home for college 20 years ago, doesn’t have feasts. It has parties, where the kebabs are mass produced in takeaway joints, the music is just as loud and kitschy, and the dancing is just as bad, but the fashion sense is much better.

This year, though, there will be none of that. Delhi is under a night curfew to keep at bay a new mutation of SARS-CoV-2, which some are calling ‘a ticking time bomb’.

Meanwhile, 1,400 km away, my hometown has the air of invincibility that only small towns possess. Durgapur calls itself Steel City, courtesy of a steel plant built in the 50s to support the industrial aspirations of a newly independent nation. The onslaught of Chinese steel has hit India’s once-proud steel industry hard. But life in this town continues to revolve around the plant and its hardy labouring class, many of whom, like my father, spend their whole lives shovelling coal into the plant’s giant ovens, inside which burns fire at 1250 degrees. In towns like this, the idea that you could be killed by a virus isn’t scary. It is ridiculous.

The change in vibe is disorienting for me. Barely 48 hours ago, I had no plans of spending New Year’s Eve here. The next time I boarded an airplane, I’d promised myself, it’d be to Amsterdam or Marrakesh, not Durgapur. That was before my father ended up in the ICU.

Don’t panic

Those are the first words my mother speaks when she calls me. “Don’t panic. Baba went to the bathroom this morning and came out unable to breathe. Don’t panic. They are saying he has pneumonia and something might be wrong with his heart, but don’t panic.”

I know that tone. It is the unnaturally calm tone my family puts on while delivering bad news to me, lest they provoke my anxiety. I am the fragile boy who needs to be handled with kid gloves. It can’t be easy for Maa to make this call — and at this time of the year.

Durga Puja, Diwali, Christmas, New Year — the holiday season has a long history of drawing out my darkest moods. Like clockwork, by September or October every year, I start becoming dysfunctional with the guilt of not feeling festive enough. I whimper before my therapist, begging her to teach me a trick — anything at all — that’d help me at least fake normalcy. I make elaborate suicide pacts with myself, and then hate myself for not following through. By New Year’s Eve, I am filled with self-loathing for being the insufferable sourpuss who pissed on everyone’s party, again.

My mother is a retired nurse who believes that there’s no sickness more dangerous than asking for space. After years of pleading, bullying, and guilting me, she has made peace with the fact that I will never be the good immigrant son who pines to reunite with family during holidays. The opposite: Holidays make me want to become invisible.

This year, she has an added reason to assume that I’d want to be left alone. I’ve just lost my job. It is the bleakest yearend of my life.

What Maa doesn’t know is that 2020, in spite of — because of — its unending shitfest has finally made me a free man. The holiday season no longer has any powers over me.

“I’m coming home,” I tell her, feeling indescribably light.

Polarisation and the end of performance anxiety

Like most mental health phenomena, holiday blues gained cultural currency as a #FirstWorldProblem. In the US, for instance, it is a well-documented scourge between Thanksgiving and New Year's Day. In one study by the American Psychological Association, while the majority of people said they felt happy during the holidays, they also reported frequent feelings of fatigue, stress, irritability, bloating, and sadness.

Thirty-eight percent of those surveyed reported heightened stress during the holidays, mostly because of lack of time, lack of money, commercialism, the pressures of gift-giving, and family gatherings. Further aggravation comes in the form of the long, dreary, and dark winter, triggering SAD, or seasonal affective disorder.

In my sunny country, on the other hand, such a thing as holiday depression was long inconceivable, even taboo — an affront to the very idea of India.

The defining mythology of the country I grew up in was a billion people celebrating each other’s festivals as one inseparable, vacuum-sealed mass. That spirit was baked into the national motto that every child was taught in school: unity in diversity. Not participating in the collective rituals of nationhood made you a bad citizen.

But that pressure doesn’t exist in the India of 2020. Festivals and holidays are no longer a sacred if sometimes overbearing expression of community and fellow feeling. They have metastasised into exhibitions of difference. Dates on the calendar that earlier reminded us to dissolve boundaries are now occasions to mark out territory.

The augurs became prominent last year, after the government passed a new law to simplify Indian citizenship for Hindu, Sikh, Christian, Jain, Buddhist, and Parsi refugees from India’s neighbouring Muslim-majority countries: Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Supporters of the law applauded it because it offered safe haven to minorities who face religious persecution in these countries. But critics pilloried it for excluding Muslims, violating India’s constitutionally enshrined secularism.

The end of 2019 and the arrival of 2020 became footnotes to an unprecedented 101-day nonviolent sit-in protest against the law in Delhi, led by the likes of the 82-year-old Bilkis, who was anointed one of TIME’s most influential people of 2020. But that couldn’t erase the memories of rioting and arson and deaths reportedly at the hands of law enforcement.

Suman (name changed), a former colleague of mine, told me before Christmas last year that she was wracked by a whole new kind of malaise: ‘political depression’.

“It’s like you’re in the middle of a gigantic storm,” she said, “and it’s going to rip you apart. But it won’t. You’re left but everything else is blown to smithereens.”

In the India of 2020, Christmas, Eid, Vaikuntha Ekadashi are not ‘Indian’ celebrations anymore. ‘We’ have our celebrations. ‘They’ have theirs.

Who knew that the antidote to my holiday depression lay in dismantling what the champions of new India call ‘sickularism’.

The year of blur

Of course, isolationism is far from being an Indian invention. In the MAGA-Brexit world, it is a global template. In 2020, that impulse found an unexpected boost via a pandemic.

The most perceptive description of the year I’ve come across is by the journalist Alex Williams in the New York Times. Williams calls 2020 “the year of blur — a year so momentous [that] also feels, in a way, as if nothing happened at all.” The world witnessed a rampaging virus, devastating wildfires, deadly floods, rousing uprisings against racism. But watching all these events pass while staying shackled to our desks and screens stripped them of their realness and reduced them to a surreal showreel.

Time and space were emptied of meaning. Did I start writing this today or last week? Does it matter?

As we drew an ever smaller and tighter ring around ourselves, sameness settled on us like a second skin. Our shared sense of time, otherwise punctuated by “boundary events” such as commutes and coffee meetings and shopping for festival clothes, lay pulped.

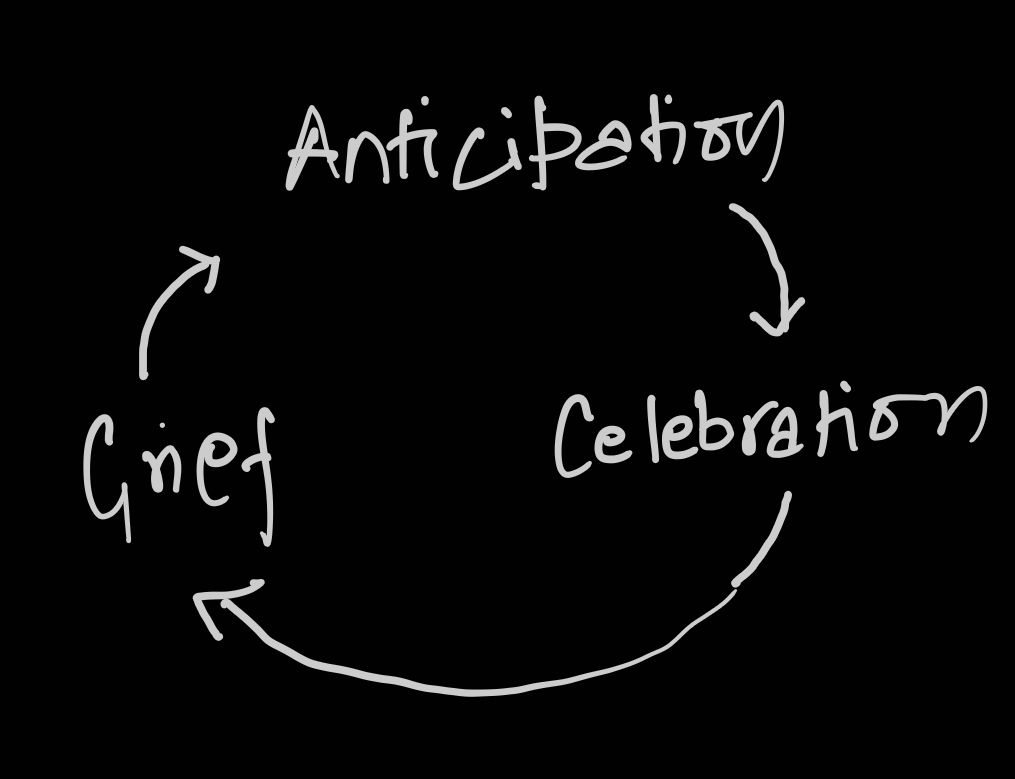

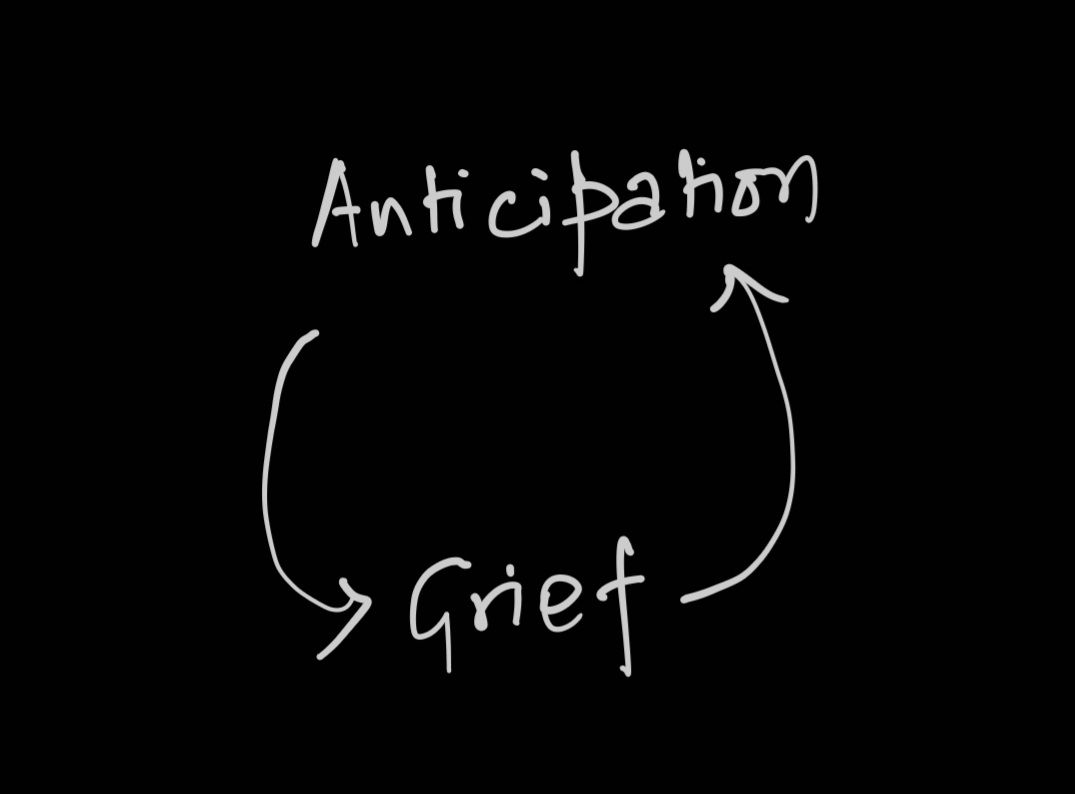

For most people, psychological time around holidays in an ordinary year has three distinct building blocks — anticipation, celebration, and grief, followed by anticipation once again. With celebration outlawed, the world was first left with anticipation and grief, and soon, as hope of quick miracles disappeared, only grief.

For those of us who neither joyfully anticipated the holiday season nor mourned its departure, 2020’s tableau of destruction brought freedom from the guilt of not acting sufficiently festive.

But it has been a Faustian bargain.

That familiar guilt has been replaced by a new, sharper kind — survivor’s guilt, the exquisite guilt that comes with the knowledge that you live while so many others are dead, not necessarily because you deserve to but because you had plenty of luck.

The view from the therapy room

Natalia Braun is a counsellor near Zurich. “The pandemic, as any significant incident or disaster, let things that are hidden in personalities and societies manifest themselves relentlessly,” she says. “For some, the holiday season was a long expected break. On the other hand, if a family has always been dysfunctional and got together not in an authentic way but because it was a social must, festivities with such a family would always be a torture, and the pandemic would have brought an excuse not to engage.”

In India’s party capital Goa, psychotherapist Nitasha Borah says several of her clients reported an improvement in mood and belief in their capacity to get through these periods. In addition to the general low-key vibe around everything, what seems to have helped is that the expectations from them haven't been the same, Borah says.

“Family members have been more accommodating because ‘everyone's in the same boat’. ‘I don't feel like doing this’ has become a perfectly acceptable answer to social obligations. Some clients told me that they feel more self-confident now because everyone can finally have a glimpse of what it’s like to struggle with daily challenges. They tend to think: At least I have some coping skills because of therapy, but others have no idea how to cope.”

This year was a palimpsest of trauma, with trauma overwriting trauma overwriting trauma. In this crowding of mega tragedies, where’s the room for puny sadnesses?

Postscript: disco lights

As I write this — I don’t have to send this post to you till January 6, but I don’t know if I will get the time later — Baba still needs oxygen to breathe. The doctors are frustratingly reticent. All we know is that he doesn’t have Covid, and that we need more tests to figure out exactly what is wrong with him.

I have a feeling I should panic, but the music is distracting me. There’s something about that song that feels like an illicit pleasure in 2020. It is a song about lust in a year of loss.

I get up to close the doors and windows so I can concentrate on work. That’s when I see it: something confounding right inside the terrace room where I am quarantining.

Disco lights.

How did these lights get here? What made my parents, from whom I inherited my inability to so much as nod in rhythm, invest in something so out of character?

I have no idea. But as I stare at the mosaic of purple, red and blue flooding the room, I am overwhelmed by affection for this room, this town and its reckless merrymakers, everything contained in this time and space that exists in spite of everything in the time and space that we are scraping ourselves off.

Ki sundor hashi tomar, haay go more jai/tomay ami bhalobashi, tomay ami chai. What a sweet smile you have, oh it kills me/I love you, I need you.

Happy New Year.

Need help? Please don't suffer alone. If you have been affected by any of the issues in this article, this website provides contact details of free helplines around the world.

A huge THANK YOU to all of you — in barely 20 days of launch, Sanity by Tanmoy has crossed 1,000 subscribers, with a growing base of paying subscribers. For a recently unemployed writer, this has been the source of such incredible validation and courage.

Articles like this require a significant investment of my time and resources. As an independent creator, I am counting on your support. Please pick up a paying subscription now to help me continue this work.