Why are kids obsessed with dinosaurs?

It tells us an important story about being human.

A has decided that the T. Rex toy we bought him from the Natural History Museum in London ("That'd be £15") is his son. I tell him I'm confused because until now I thought he was a lion, interested in raising lion cubs. A, who turned five this year, ignores me and declares that from now on, he will only go to bed after putting his son to sleep first. He squeezes my battery-operated grandchild's famously small arms, and it (or should I say he?) lets out an approving screech.

The pale-green thing with a disproportionately large head and eyes that glow a sinister yellow is the latest addition to A's vast dino library, which also includes a burgeoning catalogue of books, movies, and TV shows. As I type this, I can hear the jingle of Disney's Gigantosaurus –"Gigantosaurus/is really enormous" – playing in the living room. No other species, extant or extinct, has such a sprawling presence in our household.

I have no idea exactly how and when A developed his passion for dinos – it's as if he could always nonchalantly hold forth on the difference between a Stegosaurus ("plates on the back") and a Spinosaurus ("curved spine"), or why the Parasaurolophus had a hollow crest ("it worked like a horn"). While he still mutates into Simba the Lion when an adult's instruction displeases him, dinos have a special claim over his affections, as his latest fatherhood fantasy shows. (Bonus: It has allowed us to have an interesting conversation about adoption.)

Why do you like dinosaurs so much, A?

"I like dinosaurs because... well, when I learnt about them I just really liked them," he says in a tone that sounds like, "Duh, what kind of question is that even."

Umm okay. So what's your favourite kind?

"I like roaring dinosaurs. But my favourite are hadrosaurs even though they don't roar."

I see. And what about T. Rex?

"I like T. Rex because it's thumpy and leaves big footprints."

A's dinophilia is amazing, but it's also entirely ordinary. "As a near-universal rule, kids love dinosaurs," writes the journalist Kate Morgan. "[I]f you weren’t obsessed with dinosaurs as a kid, you almost definitely know someone who was."

"These kids can rattle off the scientific names of dozens, if not hundreds, of dinosaurs. They can tell you what these creatures ate, what they looked like, and where they lived. They know the difference between the Mesozoic era and the Cretaceous period. The level of dinosaur expertise a kid can have is seriously astounding, particularly when you consider that the average adult can name maybe ten dinosaurs at best."

This nonpareil popularity of dinos fuels a thriving global dino industry, churning out everything from T-shirts to theme parks. Enter China. In the southwestern Chinese city of Zigong, oil explorers discovered one of the world's largest deposits of Jurassic era dino fossils in the 1970s. (The Jurassic era extended between 200 million years and 145 million years ago.) Zigong now makes a fortune manufacturing and exporting 80% of the world's animatronic dinos. A five-metre-long Tyrannosaurus sells for up to 50,000 yuan, or about US$7,000.

Over in the UK, the dinosaur toy sector grew 23% in the year to May 2022 and was worth £51.6 million. A Diplodocus skeleton from 150 million years ago belonging to the National History Museum toured the country and raked in an additional £36 million for the British economy. (For comparison, Nessie, as the Scots call their beloved Loch Ness monster, is estimated to bring in £41 million annually.)

Just how did an animal that vanished 65 million years attain such superstardom? Does the awe in which children hold dinos serve an evolutionary purpose? What story about being human is it telling us?

Many a parent and social scientist has grappled with this mystery, but cracking it satisfactorily hasn't proved as easy as spotting a Triceratops fossil in Montana.

"Yup, do let us know if you find an answer to this," a friend tells me when I share that I too want to get in the hunt. "It's 24/7 dinos at home."

Spielberg and the cult of the giant dino

The appeal of dinos is transgenerational. Growing up in the 80s and 90s in a lower-middle-class family in a small town in India, I didn't have access to slickly packaged dino ware. But it didn't matter, because my generation had the Big Daddy of all dino cult starters. His name was Steven Spielberg.

It was the summer of '94. My cousin sister and I rented a video cassette player and a tape of Jurassic Park from the neighbourhood video store. We watched it on her black & white TV, shrieking in horrified delight when a venom-spitting dino ate the bad guy, and rewinding the final escape scene over and over, half in relief and half wishing there'd be one final hair-raising chase.

My curiosity was further fanned by a story I read in a popular Bengali children's magazine that came out around the same time. A Bengali boy in the US had discovered the fossil of a new kind of dino, and in his honour the entire genus was named after him! To the pre-teen me, this was a giddying, fantastical achievement.

Last week, while researching this article, I made the rather more prosaic discovery that Shuvosaurus inexpectatus ("the unexpected lizard of Shuvo") has since been declared not a dino but a 'crocodilian'. I quickly brushed aside this minor technicality, not wanting it to interfere with nostalgia. More importantly, I noted that Shuvo Chatterjee's father, Sankar Chatterjee, is one of the world's foremost dino experts. Makes sense.

Chatterjee Sr. taught in the Department of Geosciences at Texas Tech University and was the curator of paleontology and director of the Antarctic Research Center in the Museum of Texas Tech until his retirement last year. I found an email ID after some digging and decided to send him a mail sharing my childhood fanboy moment, and asking him if he has any theories on why kids are crazy about dinos.

I was thrilled when he replied after a couple of days, even though he didn't give me a definitive answer.

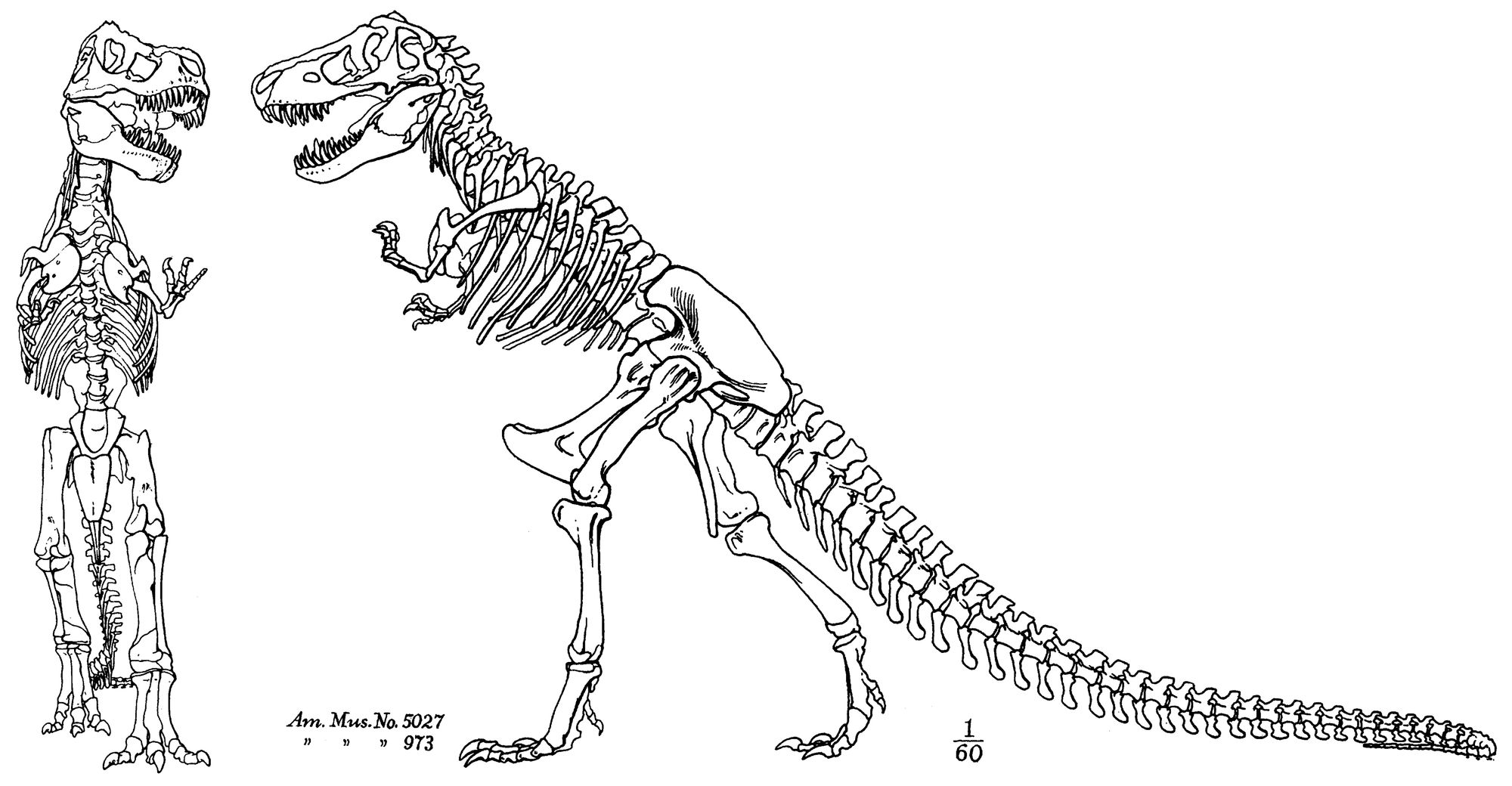

"Nobody knows," he wrote. "The immense size of the dinosaurs, their strange shape, antiquity, and mysterious death – all contribute to their mystique. Dinosaurs evoke awe and imagination in young and old alike; they bring back strange, lost worlds to us. They are the dragons of [our] dreams, non-threatening monsters in the museums. Unlike monsters in fairy tales, dinosaurs are real and larger than life."

The subject of dinos' massive size is a recurring and obvious one in this discussion. A particularly intriguing idea floated by Tom Whyman, philosopher and father of a three-year-old, is that dinos belong in the same class of large things – also including cars, buses, trucks, and planes – that tend to fascinate kids, perhaps because they remind the primitive part of their brain of the 'big game' that was an integral part of the lives of our hunter-gatherer predecessors, and that has disappeared in modern society.

Considering the notoriously gendered ways of the toy industry, it's possible that dino marketers specifically target young boys with their hulking, masculine presentation. When Lisa Wade, a sociology professor, called out a dino toy seller for creating a separate section dedicated to 'dinosaurs for girls', it led to a lively debate and a thoughtful reply from the company, pointing out the difficult balancing act of running a gender-free site with the gendered expectations of parents themselves.

My next port of call on the question of size: child psychologists.

"I'm not sure, but my psychotherapy instinct says it's all about feeling big, scary, and powerful in a Gulliver world?" speculated psychotherapist Karolin Susan. "Making noises, rawr-ing, shouting, screaming, talking fast are all great stimulation mechanisms as well. It fulfills their sensory needs, it calms them."

Aha. That'd explain why A is attracted to 'roaring dinosaurs' (or indeed, lions).

Then there's a more macabre possibility: To a child, the huge mythical monster is the embodiment of the 'other', of a primal terror arising from the depths of the psyche, said Lawrence Barrett, who's a Jungian coach. "They are the lived symbol of the child's experience of the world, surrounded as they are by huge and unfathomable creatures," Barrett said. "By demonstrating that we can master our fears in proxy or symbolic form, we build agency. This is why people enjoy horror films."

Films are of course key to dinos' pop-culture clout. Jurassic Park went on a worldwide box-office rampage upon its release in 1993 and became the highest-grossing film in history, replacing Spielberg's 1982 blockbuster E.T. Globally, the Jurassic Park franchise, with six movies and a clutch of short films and animated series, boosted interest in the arcane science of palaeontology and created a brand-new market for dino tourism.

It also cemented the larger-than-life stature of dinos in popular imagination: A size comparison of the various dinosaurs shown in the films reveals that the franchise is dominated by ginormous animals, led by the Brachiosaurus which tipped the scales at 50 tonnes. (Compare that to the Compsognathus, among the smallest carnivorous dinosaurs, which grew to only about the size of a chicken.)

Chatterjee Sr. would have you believe that their mountainous build doesn't mean dinos are brutish creatures without the possibility of tenderness. "Place your head in the jaws of Tyrannosaurus; you create a bond with this fearsome predator. You tenderly touch a Brachiosaurus's giant femur or thigh bone, as if adoring a child," he wrote to me, adding that there might be a subtler and simpler reason for children's love of dinos: All their names end with -saurus. "Kids love to remember the names because of the mnemonic quality."

Whose dino is it anyway?

In the cornucopia of dino-related literature on the internet, an important subplot remains muted: how the west created – and hijacked – the dino cultural-industrial complex.

Lukas Rieppel, who teaches history at Brown University, writes how late-19th century US capitalism turned dinos into a mass spectacle as part of a clever socioeconomic project:

"Although the economy was booming, American capitalism was in a state of crisis during this period. The industrial juggernaut was responsible for unprecedented levels of economic growth, but it also produced frequent financial panics and economic depressions. Working people were especially hard hit during these downturns, and inequality rose sharply.... Fearing a backlash to their corporate might, America’s industrial tycoons became avid philanthropists to uplift and educate working people, establishing universities, art galleries, and natural history museums, with their prized possessions, dinosaurs."

The establishment of monumental natural history museums showcasing giant dinosaur fossils in turn fed into the idea of American exceptionalism. It was a win-win.

A similarly little-known story is how India has abundant fossil wealth and supplied some of the world's earliest and most exciting dinosaur fossils, but a combination of colonial exploitation and post-colonial apathy denied it the attention it deserved.

As a result, a generation of Indian children grew up with very little knowledge of their own indigenous dinosaurs, writes the journalist Kamala Thiagarajan. Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops continue to hog the limelight, while our majestic native dinos – the Rajasaurus or the Jainosaurus – remain in the shadows.

A few creators have tried to address this imbalance. Notable among them is Vaishali Shroff, whose 2018 book The Adventures of Padma and a Blue Dinosaur aimed to make children 'fall in love with our country's dinosaur fossil heritage and to make them aware of the fact that dinosaur fossils could very well be in their backyards'. Take my money already.

Parenting win

As I researched and wrote this story over the past few weeks, I made peace with the fact that there's no single neat answer to the question I began with. I also decided that such an answer is unnecessary, because why should fun have to explain itself in a world where it can be so scarce?

I also realised with a pang of melancholy that what started me off – my son's love of dinos, which gave me a chance to recreate with him a happy sliver of my own childhood – could be running out of time.

According to child development experts, 'intense interests' of this kind usually exist between ages two and six. This is when a child will spend inordinate amounts of time devouring information about the object of their interest – apart from dinos, they are known to be into medical equipment or even blenders – and trying to master its every aspect. Usually, this deep devotion to one thing dies out when they start school and competing interests take over.

One day, during a break from work, I invite A to look at dino pictures with me. I am writing about how much you like dinosaurs, I tell him. Is there anything you want me to tell the people who will read this? About how you have so much fun with your dinos, but then you are also a lion with a big mane?

"Tell them what you told me," he says. "A is a human being, and he can change into anything he wants to be."

I wait for him to leave the room, then thump my chest and break into a roar.