The life-saving case for cash transfers

This could well be the most important question in the post-pandemic world: can putting money in the hands of people prevent suicides?

Trigger warning

Contains references to suicide and suicidal ideation.

Thanks! - Tanmoy

Daiane Borges Machado was born in a poor neighbourhood in a small town in Brazil. Her father saved up all the money he could to send his children to an expensive school. She would go on to get a PhD in epidemiology and population health from the London School of Tropical Medicine and work as a research fellow at Harvard Medical School.

Machado's expertise lies in investigating the socioeconomic dimensions of mental health and suicide – a career choice influenced by her childhood in Brazil, a low- and middle-income country (LMIC). She is an authority in the field, having worked in it since 2007. But even she couldn't have predicted just how urgent and sought-after her work would become a decade and a half later.

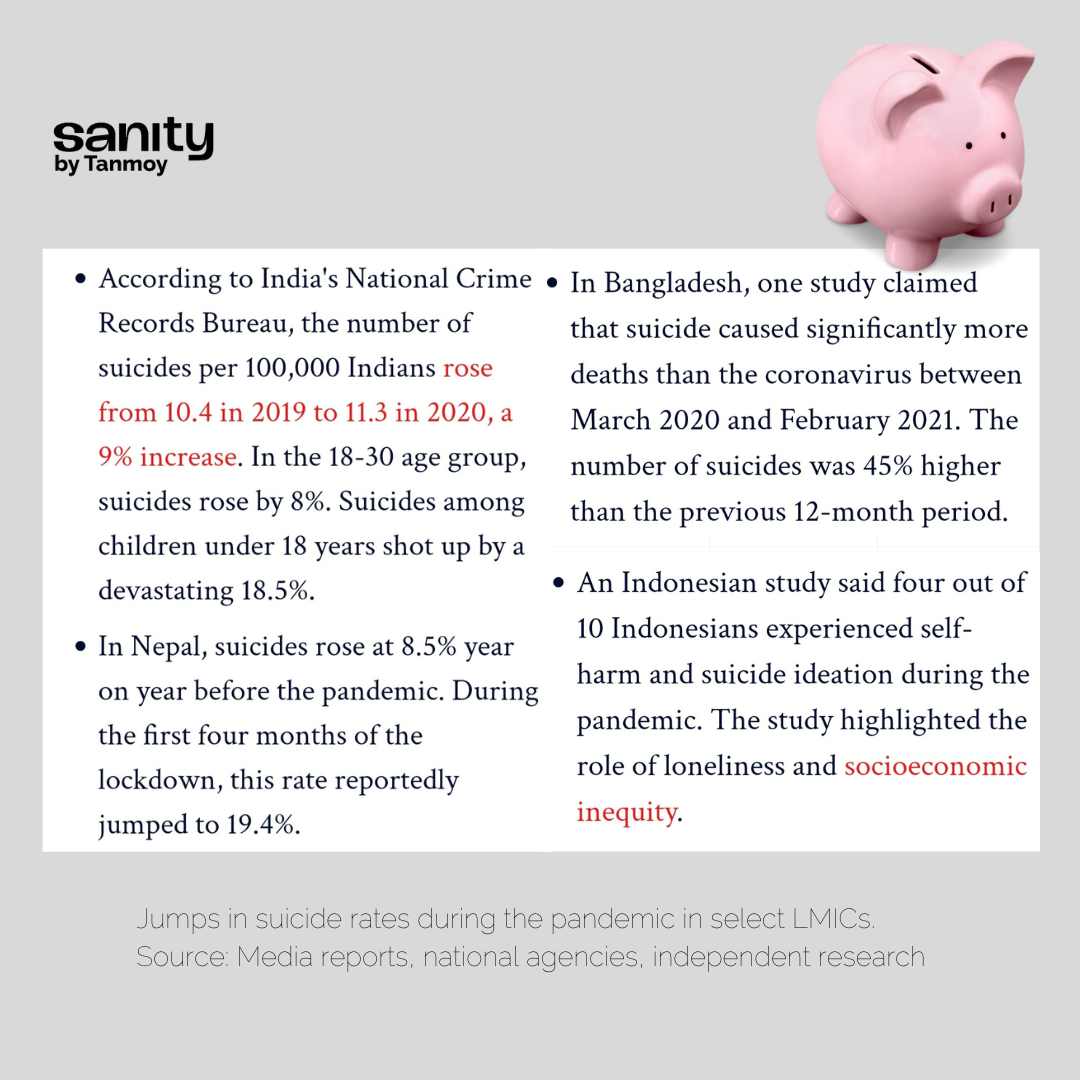

Before the pandemic, LMICs accounted for more than 77% of all suicides in the world. Data emerging from the worst waves of the pandemic, as I reported in the opening piece of this series, is chilling, with countries from India to Kenya reporting sharp spikes in suicide.

"The place, the sex, or the colour that you are born with determines way more about our lives than we believe," Machado told me last year during the height of the pandemic in Brazil. "I remember witnessing since very young how differently each of my childhood friends lived. When I went to visit my friends from school, we'd eat yoghurt, fruits, and biscuits in their houses. But when I visited a close friend Bibiu, daughter of a constructor who lived in a tent down the street, we ate flour burnt with oil, a mixture with zero nutrition."

"How can we expect people who have always eaten differently and have had different access to education, health, etc, to perform all the same in life?"

That question is at the heart of one of the most exasperating (non-)debates in all of public health, and particularly within the suicide prevention movement:

Is human endurance in the face of adversity an exclusively biomedical issue, or a social and economic one? Are people always driven to despair because they are 'mentally ill', as popular wisdom would have us believe? Or is that a copout because as a society, we have failed to address discrimination, inequality, and poverty?

The evidence couldn't be clearer. Suicide is a complex, multifactorial public health crisis with prominent and intersecting social and economic triggers. "[But] the notion that suicide is caused by depression is so strongly established that even educated health professionals try to fit every suicide into this model," says suicidologist Said Shahtahmasebi.

When this notion informs policymaking, it results in distorted priorities ("We need more psychiatrists!").

It incentivises the search for a 'suicide gene' in lavishly funded western institutions – yes, that's now a thing – mimicking the endless hunt for a 'depression gene'.

And it sucks away attention from the oppression of marginalised and vulnerable communities, fractured interpersonal relationships, domestic violence, broken education systems, and – as the pandemic has unleashed at a harrowing scale across LMICs – threats to livelihoods.

How does financial insecurity affect suicide rates? High-income countries (HIC) have produced plenty of research establishing a strong causal relationship between the two, especially in the aftermath of economic downturns, such as the 2006-08 financial crisis. It is axiomatic that a financial safety net could play a strong protective role against suicide risk. But in LMICs, where a vast section of the population permanently lives in financial precarity, this factor has been poorly researched. The absence of robust evidence has stymied demands for better suicide prevention frameworks and policies that aren't fixated with mental illness.

Machado and her colleagues challenged that in early-2021, when they published a groundbreaking paper on the impact of Bolsa Familia, then the world’s largest conditional cash transfer programme, on suicide rates in half of the Brazilian population. In sheer scale, the study was unprecedented. And the results were dramatic.

Bolsa Familia gave out BRL89 (about US$17) per month to the country’s poorest families with monthly per capita income under BRL70, or BRL140 for families with a child, an adolescent, or a pregnant woman. Recipients had to make sure that all children in the family had a minimum 85% school attendance. Women and children were required to attend healthcare appointments and follow all vaccination schedules.

Here's the crux of Machado et al's findings:

“The COVID19 pandemic is expected to lead to a severe global recession, increasing poverty and resulting in massive unemployment worldwide, with possible increases in suicide rates in the coming years," the authors added. "Suicide prevention interventions [such as this] may help to mitigate this increase, if proven effective.”

The study came as rare validation for suicide prevention advocates in other LMICs with comparable socioeconomic realities, who have long resisted the pathologisation of suicide.

"When I first saw it, I was not surprised but pleased to see some evidence," says Soumitra Pathare, director of India's Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy (CMHLP). "What did surprise me was the magnitude of the effect – 61% is huge for any intervention in suicide prevention."

As a lay person, I reacted differently to Machado's research. I have lived with suicidality and self-harm and survived suicide in my close circles, including some people living with financial hardships, and I have seen how draining it is to convince families that these deaths were even preventable. The fatalism with which society responds to each suicide death makes me angry. After all, what could we have possibly done to solve a problem that was only in the dead person's head, especially if they were also desperately poor?

At the cost of sounding mawkish, Bolsa Familia gave me renewed hope that sometimes all it takes to save a life is 17 dollars.

Was Brazil a fluke? Or, understanding how cash transfers really work

To be sure, cash transfers are not a silver bullet for racism, casteism, homophobia, transphobia, and other social ills. Bolsa Familia isn't above criticism, neither can its success in reducing the likelihood of suicide be taken for granted in other LMIC settings. ('LMIC' itself is a vast and far-from-homogeneous category.)

Cultural context is important in the aetiology of suicide, and what works for one country may not automatically work for another. There is still a dearth of research from the world's poorest countries, such as those in Sub-Saharan Africa, and from countries with the highest rates of suicide (eg Guyana), researchers Jason Bantjes et al have pointed out.

With those caveats, results from experiments with cash transfers in a few other LMICs offer strong reason for hope. In South Africa, Julius Ohrnberger led the first study in an LMIC that analysed the vital underlying mechanisms, or mediation effects, of cash transfers on the mental health of the poor adult population. The study published in 2020 found that the cash first helped unlock improvements in physical health, which in turn set in motion a virtuous cycle:

"Poor individuals invest the marginal income gain in better lifestyles and better physical health which translates into better mental health. The improvements in the lifestyles and physical health, such as reduced symptoms of illness or more physical activity, then translate into improvements in mental health, which affects working time and income generating activities positively. This can have important implications for both mental health and anti-poverty policies in LMICs."

While research on the impact of cash transfers specifically on suicide in LMICs is limited, a phalanx of case studies from widely different contexts show it can take the edge off several important risk factors.

In rural Mexico, a scheme called Programme Opportunidades was associated with a 10% fall in depression among mothers. A study of cash-reinforced therapy in Liberia noted a decline in crime and violence and anti-social behaviour among men. In the Social Cash Transfer Programme in Malawi, there was a drop in depression symptoms among youth, particularly girls. And in India, the Janani Suraksha Yojana was associated with an 8.5% reduction in maternal depression.

In Brazil, women were the recipients of the benefits, which increased empowerment and independence among them. Qualitative studies have shown that cash transfers are also correlated with decreased domestic violence and increased screening for violence victims as well as referrals and assistance for those in need, Machado said.

Among the young, cash transfers could counteract the lack of financial stability and the inability to get a job or even go to school, she explained. It reminded me of the student of an elite college in New Delhi who died by suicide during the first wave of the pandemic because she couldn't afford a laptop for online classes.

A case for universal basic income?

The success of targeted cash transfers in improving wellbeing indicators feeds into the larger debate about whether governments should guarantee citizens an unconditional universal basic income (UBI).

The idea of free, no-strings-attached money was first proposed by 16th century philosophers, but for much of history, it was seen as a wacky 'communist' fantasy. It gathered renewed momentum in the wake of modern threats to employment, such as automation. Basic income trials of varying scales have since popped up across the world, from the US to Finland to Kenya, with encouraging public health outcomes.

Meanwhile, critics attack basic income as fiscally imprudent and morally objectionable. They see in it a recipe for turning people lazy and shrinking labour supply to the economy. This isn't necessarily backed by data, even in LMICs such as Iran which has had a long-running basic income programme.

But for champions of basic income, this is no longer a debate about data.

“We have more than enough data now to prove that cash works,” says Aisha Nyandoro, who is associated with a basic income project aimed at low-income Black mothers in Jackson, Mississipi, in this excellent MIT Technology Review article by Eileen Guo. The question we must now ask is, “What is the data or talking points that we need to get to the policymakers ... to move their hearts?”

What would it take for those in power to look at security for the most disadvantaged not as a bureaucratic or logistical or fiscal question alone, but as a rights-based one? We are living through a moment in history when this should be a facetious question. What more could it possibly take if even a pandemic (coupled with devastating climate change) isn't enough?

In a preliminary study of the effects of a large-scale basic income exercise in Kenya during the pandemic – "Transfers significantly improved well-being on common measures such as hunger, sickness and depression in spite of the pandemic, but with modest effect sizes" – economists Abhijit Banerjee et al cite data that hints that a global inflection might be under way.

Between March 20 and September 18, 2020, 212 countries introduced 1,179 new social protection measures covering an estimated 1.8 billion individuals. Cash transfers made up a large share of this expansion, reaching 1.2 billion individuals. Data on how these programmes impacted suicide and related risks could be the hammer that the nail has been waiting for.

Machado would remind you though that when you zoom out from the thicket of academic papers, you see where the obvious onus for change lies. "We provide evidence," she told me, "but if the policies are not put in place, the poorer will keep paying the price."

"People don’t think much about [these issues]," she said. "People from the middle or upper class don’t think because they don’t have much contact with people with very limited resources, they don’t go into their houses. Poor people don’t think much about it either, because often they also don’t have much idea of how rich people live. We all go about our lives in our bubbles. I hope these scientific results at least give us [an impetus] that something needs to be done, and that mental health is much broader than only delivering [medical] care."

PS: Months after my correspondence with Machado, Brazil's government ended Bolsa Familia and announced a new, bigger social welfare measure. It is too early to discern results, but the new plan has been criticised for not being indexed to inflation.

Need help? This website provides contact details of free helplines around the world.

Bolsa Familia card image: Jefferson Rudy/Agência Senado

This story is part of a special series on suicide prevention, supported by Mariwala Health Initiative. Click on the banner below to explore the entire series.

Donate any amount you can by clicking here (for Indian donors) or here (for international donors).

Or pick up a monthly or annual subscription.

Thanks! - Tanmoy